My mother, Carla Bosch, was born in 1946 in a displaced persons’ camp in Bucholtz, West Germany. Her father was loving; her mother was cruel. After WWII they moved to Amsterdam, Holland, where they lived until my mother was 11. Then they moved to the states. The school district bumped her up two grades. I know little about her life during her teen years except that her mother constantly called her “ugly,” and if she showed signs of angst, her mother checked her into the psych ward at the local hospital.

In 1965, my father and mother met in a pizza parlor in Binghamton, New York. She said he looked like Woody Allen with black hair. They started dating and within several months, she became pregnant with my brother Tony. My parents married in Nov. 1965, spent their honeymoon in Cooperstown. Then they moved into a rented house on the south side of Binghamton. Tony Jr. was born in May 1966, and slept in a toy chest. My parents paid for diapers by hustling pool at local taverns.

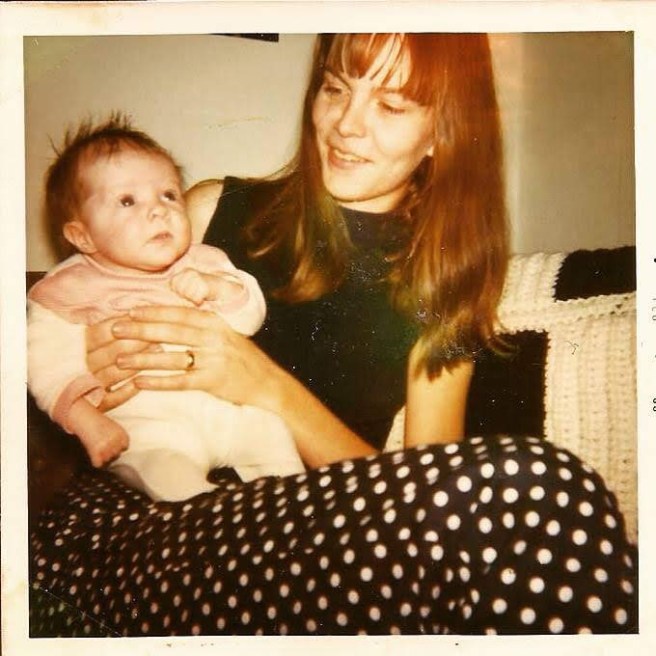

My father doted on my brother, however, he was not a man easily tamed. He believed women stayed home, and men went out partying. In an attempt to keep him out of the bars, my mother became pregnant with me. No matter how cute I was, and I was cute, her plan failed. She started leaving my brother and me with sitters, and according to gossip, sometimes alone. When I was six months old, my father kicked her out of our house, filed for divorce, and took full custody of my brother and me. He told her never to contact us again.

Growing up, Tony and I were not allowed to talk about “Carla” in front of my stepmother who insisted we call her “Mom.” And if I asked my father’s family about my birth mother, they said, “She left you. You don’t want to know her.” But I did. There were only about five photos of her in the entire house. I studied her high cheekbones, green eyes and square chin. Did she ever think about us? Where did she live? And when I walked around town, every woman I saw was a possibility. Is that her? Is that her?

As I came of age, I tried to make peace with not knowing my mother. Tony always said, “Don’t bug Dad with your questions.” But, Tony was three when she left! Surely he had some memory of her. He said he remembered her throwing a plate. And that she taught him to read. But I had zero. Not a voice. Not a scent. Not an image. I stored a few memories of the women my father dated before he married my stepmother.

After I graduated from high school, Tony was killed in a motorcycle accident. That cemented my dislike of my stepmother. In 1989, I joined the navy. Perhaps, I thought, if I “traveled the world,” I might eventually find our mother. In 1992, while stationed in Monterey, California, I became pregnant. The doctor asked, “Did your mother take drugs when she was pregnant with you?” I said I didn’t know. He said, “Can’t you ask her?” I shook my head and waited until I got into my car before I cried.

One night while I was nursing my daughter “Jessica” and watching the news, a segment called Finder on the Money explained “How to find a long-lost relative.” I took down the number. They put me in touch with a private investigator. And though I knew my mother’s name, birth date, and birth place, he said he needed her social security number.

I ordered my birth certificate, and my parents’ social security numbers were on it! Within a couple of days, the investigator called with my mother’s address in Newport, Rhode Island. I drafted a letter. “Hi, Mom. It’s me. Your daughter Cynthia. Do you want to know me?” Then I bought a pack of Marlboro Reds and chain-smoked while waiting for her response.

In her very first letter she asked me to imagine being a 21-year-old mother, pregnant with her second child, surrounded by the tumult of the late 1960s–the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The Vietman War. And then she asked, “Does your brother want to know me?” I had to write back and tell her Tony was dead. She sent back a short note: “How tragic. I broke my glasses. More later.” I can’t imagine the guilt she must have felt — leaving us behind — knowing she would never see Tony again.

Several months later, my mother and I made plans to meet in Binghamton. I was 24. She had gotten remarried the year my brother was killed and was bringing her husband Bill. I had to keep the entire thing secret from family, because my father would not be happy. (A friend dropped the dime on me, and I got an earful from my dad. See earlier post–Secrets Cause Cancer.)

My mother and I met at a restaurant that no longer exists. It was encased in glass, and I saw her before she could see me. I looked in and waved, and she got up from the table to greet me. My mother is 5 foot 11, with salt and pepper hair cut in a bob. She wore a linen blazer and long skirt. She leaned over and gave me a half hug, then invited me to sit with her and Bill. He stood to shake my hand. He had black hair and glasses, and an inviting smile.

The dinner conversation was superficial. With Bill there, I was hardly interested in poking into my mother’s reasons for leaving. However, when he left the table, she said she was sorry she left. I didn’t quite know how to respond, except to say Thank you. One thing I did appreciate was that my mother wore silver jewelry, which was also my favorite. At the end of the dinner, I went to where I was staying. The next day, before they left town, my mother and Bill stopped by to meet Jessica. And then they were gone.

Now, my mother and I are pen pals. She does not have a computer. She does not have a cell phone. She will never travel to Idaho. I send her a birthday card every August, and an Enjoy Your Day card in May. At this point, we will never be best friends. However, I am glad I got to meet her. My father made his peace with it as well. I’m hoping someday we meet again, but I have no idea how that might happen.

nk I had the affair because I had been feeling tossed aside and insignificant in the marriage, but didn’t have the skills or faith in Eric to tell him. So, instead, I lit a fire underneath our relationship, which sent him running. I even dated the guy with whom I’d had the affair (it was a disaster), adding insult to Eric’s injury.

nk I had the affair because I had been feeling tossed aside and insignificant in the marriage, but didn’t have the skills or faith in Eric to tell him. So, instead, I lit a fire underneath our relationship, which sent him running. I even dated the guy with whom I’d had the affair (it was a disaster), adding insult to Eric’s injury.