Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

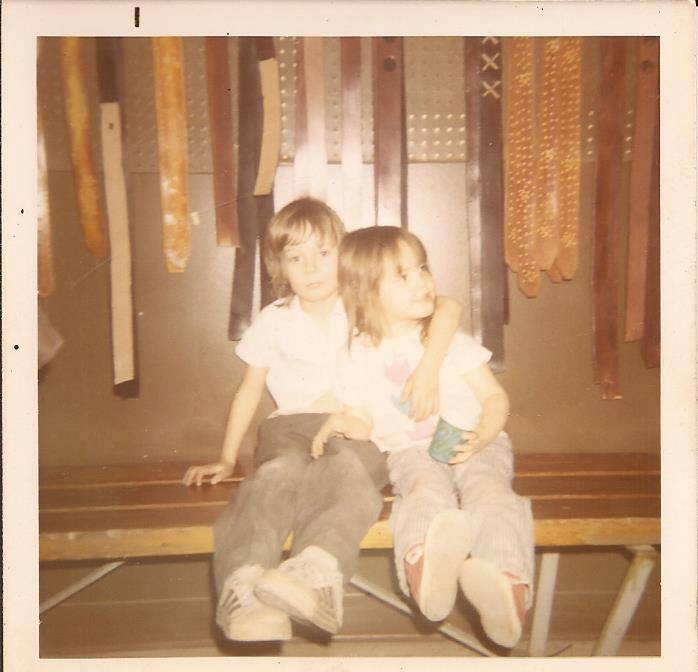

For the past couple of years, I have been working in earnest on my memoir, named like this blog: The Cobbler’s Daughter. Loyal readers, and beloved editors from LCSC, WWU, and UI, you probably know that it is a childhood memoir, involving the very close relationship I had with my older brother Tony. Here we are in my father’s store, The Leather Shoe Shop, around 1971. We are five and three.

I love that Tony has his arm around me, because this is how I remember him–big brother, protector, always close. And that’s why it is taking me so long to finish the book. My brother was also troubled–and I don’t want to give away too much, because I’m going to want you to read the book once it’s finished. Let’s just say, we grew up in the 70s, and the full title is The Cobbler’s Daughter: A Gen X Memoir of Sex, Drugs, and Rock ‘n Roll.

Please be patient with me, dear friends, and know, I will return to this blog with more current events. Right now, I’m kind of stuck in the past.

All my love, Cindy

It was May of 1987. I was 18, and my brother Tony had just turned 21. We were hanging out with a few friends at my apartment. In my white stretch jeans and loose hanging sweatshirt, I stood in front of the small group telling them stories about my and Tony’s childhood in our father’s shoe repair shop. After 16 years, our father was preparing to retire and Tony was going to take over the family business. He said I could work at the shop with him.

During my make-shift stand-up routine, I talked about the time Tony and I got lost in the woods on a day-camp hike. We were both bawling and eventually found our way back because I remembered the InchWorm toy smiling in front of a run-off valve. I talked about the massive Easter egg hunts with our 12 cousins at our grandparents’ house. And, how we took scraps of leather, wet them under the tap, and stamped our names in the hide with brass tools.

During my make-shift stand-up routine, I talked about the time Tony and I got lost in the woods on a day-camp hike. We were both bawling and eventually found our way back because I remembered the InchWorm toy smiling in front of a run-off valve. I talked about the massive Easter egg hunts with our 12 cousins at our grandparents’ house. And, how we took scraps of leather, wet them under the tap, and stamped our names in the hide with brass tools.

I started to walk toward the kitchen to get another beer. In this particular apartment, you had to walk through the bedroom to get to the kitchen. Imagine! I hadn’t noticed my brother followed me. Tony had silky brown hair, bright green eyes, and freckles. He was wearing a brown leather jacket. “Hey,” he said, “you made me cry when you told those stories.”

I smiled. That made me so happy. Usually my main goal was to make him laugh, but if I moved him that much. Wow!

“You’re the most important woman in my life,” he said. “I love you.”

Gulp. I looked at my white leather elf boots. I felt so embarrassed. My brother had called me ugly the first nine years of my life. We used to fist fight in earnest during middle school. And, since he had been in the army for two years, we hadn’t been around each other that much. I barely eked out an “I love you too.”

“We are going to have so much fun working together in the shop,” he said. “We’ll be party buddies for the rest of our lives.”

* * *

Two days later, Tony and I had brunch at Friendly’s restaurant. We hung out for most of the day at his place, and then he drove me back to my apartment on his motorcycle. We had a couple beers and listened to Run DMC’s Raisin’ Hell. At around 8 p.m., Tony left on his motorcycle to go to the store. I fell asleep on the couch. Three hours later, I was awakened by the phone, and the soft voice of my uncle Joe saying, “Tony was killed on his motorcycle tonight.”

As you might imagine, my life was forever changed throught that experience. I went from being a carefree 18-year-old party girl to a full-on grieving woman. A woman who cried every time someone said the name Tony. A woman who threw up when she ate. A woman who jumped at the slightest noise. A woman who was certain the ghost of her dead brother would visit to tie up loose ends.

Why had I been so afraid to tell Tony I love you? He was my brother. My rock. My shield. The first boy I ever loved. And, he had invited me to work with him at our father’s shop!

So, today, if I love you, I tell you. Tony’s death was a precious lesson. He was 21. He would never grow old. That taught me how short life is. In 1987, I started to tell my family, my friends, and even acquaintances “I love you!” And you don’t even have to say it back.

My older brother Tony turned 21 on May 1, 1987. He came to my apartment, and my roommate and I threw him a small party. We drank Michelobs, and I told stories about Tony and me from the old days when my father owned The Leather Shoe Shop.

One memory is of Tony and me, holding hands, watching a fight between our father and his girlfriend Cathy. She slaps Dad’s eyeglasses off his face. In another, Tony and I walk along the sidewalk at the Vestal Plaza amid a frighteningly loud thunderstorm. I’m bawling. Tony has his arm around me, and repeatedly pats my shoulder, saying, “It’s okay, Cindy.” And in another, I’m on my tricycle, and he nudges me down a steep hill. I remember nothing after the crash, but for a week, I had one hell of a shiner.

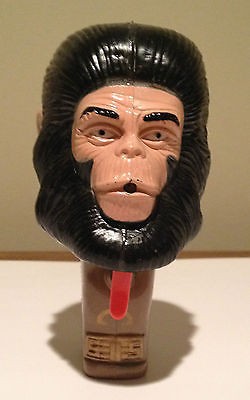

When I was four, Tony talked me into stealing a Planet of the Apes squirt gun from Grand Way department store.  Of course he didn’t say, “Steal.” He said, “Take.” We walked back to the shop where my father’s new girlfriend interrogated me and promptly dragged me back to the store to admit what I had done. The next time we visited Grand Way, Tony handed me a Magic 8 Ball, and said, “Slip this in your sleeve.” Without hesitating, I said, No.

Of course he didn’t say, “Steal.” He said, “Take.” We walked back to the shop where my father’s new girlfriend interrogated me and promptly dragged me back to the store to admit what I had done. The next time we visited Grand Way, Tony handed me a Magic 8 Ball, and said, “Slip this in your sleeve.” Without hesitating, I said, No.

The stories made him laugh. Sometime during the party, he pulled me aside and said, “I love you. I’m looking forward to spending a lot of years hanging out together.”

As kids, Tony was timid; I was hyper. When my father brought out the video camera, Tony hid and I danced around. When I complained to Tony about our stepmother’s abuse, he said, “Just keep quiet.” He never complained. Instead, he started smoking cigarettes and pot, and drinking at 12. When our stepmother slapped him, he stared her in the face and took her abuse. I screamed when she hit me, hoping the neighbors would hear and call the cops.

Tony and I rarely fought with each other, but when we did, it was about the dumbest things. I hid the remote so he couldn’t change the channel, and he punched me until I gave it back. I called him a “Buck-Toothed Beaver.” I punched him in the arm as hard as I could, and he stood motionless, then said, “Did a fly land on me?” But, if I wanted to send him into a rage, I sang “opera” at the top of my voice. I laughed so hard his punches were painless.

By the time Tony and I were in high school, there were no more fights. We became allies fighting against a common enemy. “If you don’t tell Dad you saw me smoking, I won’t tell him you were with a boy, and not at the movies.” Deal.

In 1983, after coming home drunk too many times, running away from home too many times, and getting kicked out of high school, Tony joined the army at the urging of my father and his wife. Tony earned his GED in the military and was relegated to being a cook. After two years, he was done. He moved to California, fell in love with an awesome young woman named Erika and came back to New York.

I was delighted. Tony planned to take over my father’s shoe-repair business, and he told me I could work there too. I could quit my job at McDonald’s and have a career. Tony and I were going to be together again! For the first time in years, our family spent Christmas together.

Two nights after Tony’s 21 birthday, my uncle Joe called and told me Tony was killed on his motorcycle. He’d been riding to the Great American grocery store on Main Street in Binghamton, our hometown, and was struck by a red Dodge Demon. Tony died instantly. My father and his wife were on an emergency flight back from Florida where they had been looking for a house.

Because I was 18, I had zero coping skills to manage my grief. All I could think was How could he do this to me? He was abandoning me. I would have to live without him and deal with my stepmother alone for the rest of my life. How would I get through this? I took a cab to my paternal grandparents’ house, so I could be with my family while we waited for everyone to get the news.

That night was a blur–falling asleep on my grandparents’ couch, crying, listening to the grief-stricken wails of my relatives, watching the EMTs fail at giving Tony CPR on the TV news. My father called from an airport and asked how I was feeling. All I could say was “What are we going to do?” He said, “It’s gonna be all right.” When he and his wife returned to Binghamton, I stayed at their house, and slept in the extra bed in my 11-year-old brother Jack’s room.

There was the wake, the funeral, and the burial. It was raining like hell that afternoon, and the cemetery was all mud. Beneath the sagging tent, my entire family gathered in folding chairs. I sat beside my father and held his hand. When they lowered Tony’s coffin into the ground, I started sobbing. He was my only witness to our abusive childhood. The truth about Dad’s wife and how she treated us was buried with him.

When I interact with people who have an acrimonious relationship with their sibling or siblings, I’m often surprised and sad. Tony was my best friend, and for 18 years I worshipped him. He’s been dead for almost 32 years, and I’d give anything for five more minutes with him. They say the strongest bonds are forged in fire. Our chaotic childhood bonded us for life. His impact on me was profound and lasting, and I still think about him every day.

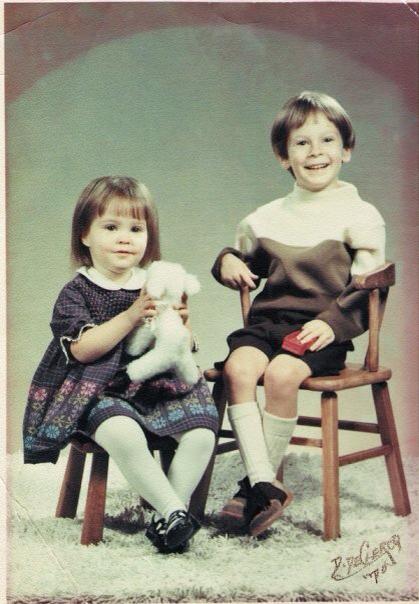

My mother and father split up when I was six months old, so my experience with the broken family started early. My first memories include my father, my older brother Tony, and many members of my large extended family. We are Italian-Americans from upstate New York, and except for mafia ties, we live up to the copious stereotypes: loud, romantic, passionate, beautiful, dramatic.

In 1975, my father remarried. I was six and Tony was eight. It was a different time, and we were not invited to the wedding or reception. In fact, Tony stayed with a friend, and I stayed with a friend of my stepmother’s. And although I don’t remember the woman’s name, I do remember playing the piano, and incorporating “turd” into an impromptu song. She yelled, “Hey! We don’t use that kind of language in this house.”

Six months after the wedding, my father bought us a house on the west side of Binghamton. My stepmother was 19, Tony was 9, and I was 7. My baby brother was 9 months old. We were told he was a “preemie” — but he weighed six pounds, six ounces at birth. You do the math.

Tony and I started at a new school. Although I wasn’t sure how we were different from other families, I knew we were different. My father was a shoe-repair man who owned a cobbler shop. Instead of wearing a suit to work, he wore denim and leather. My stepmother was a stay-at-home mother who wore no bra beneath her T-shirts, had Farrah Fawcett hair, and marble blue eyes. One of the young men in our neighborhood asked her out.

Mine was not a peaceful childhood. There was a lot of fighting between my father and stepmother about Tony and me. She was intensely jealous of anyone stealing attention from her. She was a screamer. My father was slow to anger, but once he broke, look out. And while he was not quick with the belt, she was. Any small thing could set her off–pots and pans “shoved half-assed in the cupboards,” food splattered on the floor, a crass remark. And she hit in public.

Tony started running away from home at age 14. I hid in my bedroom with books, TeenBeat, and sketchpads. My younger brother was beaten so often that when I reached to touch him, he ducked. When my father was home, my stepmother never yelled or hit us, and spoke with a sickeningly sweet voice. When my father was gone, she was a ticking bomb ready to go off at the occurrence of spilt milk. To this day, when I meet a person who reminds me of my stepmother, my antennae lift in response. And I have a sincere distrust of people who bully children. A therapist I saw for a while told me, “You have strong feelers for a reason. Trust them.”

In 1998, my father divorced this wife, after two decades of her infidelity, fighting, and confession that she stuck around for the money. One day I asked him, “Why did you stay so long?” He shook his head. “Ah. When you and Tony were small, whenever I saw your messy hair and dirty faces, it broke my heart. I wanted you to have a mother.”

The decisions we make out of love, or what we think is love, are often ill-fated. Self-delusion has to be one of the most powerful tools of the mind. Think here of the spouse of the serial killer who says, “I never knew.”

My first pregnancy and marriage was at age 23. It took me less than two years to rip that apart and create what I loathed–a broken family–all because some guy said I was his true love. Luckily, my ex-husband Jeremy is not a grudge holder, and we are still friends. God bless that guy.

Something about turning 50 has made my brain go wonky. I keep having dreams about my two ex-husbands, and my late husband, and I spend a lot of time wishing I had done things differently. Perhaps made decisions based on logic instead of “love.” Regret, coulda, shoulda, woulda, etc. Because of childhood abuse, I have been in therapy most of my adult life, and I am still working through a lot of the muck.

The therapist I’m seeing now is helping me connect the pain of my current heartbreak over losing Eric and the chance to rebuild our family with the lingering issues from my childhood. It’s a scary process, however, I’m determined to reach a place of peace and happiness. It’s easier to run away–drink, have sex, ignore your kids, and pretend everything is great. But at this point, I’m way more interested in doing the hard work if that’s what it takes to become unbroken.

My father was not the best at picking women. My biological mother who was “the most beautiful woman he had ever seen” became pregnant several months into their dating. They married, had my older brother, and fought all the time. I’ve heard both sides of the story and my interpretation is this: My father was a good-time Charlie, and my mother was a feminist. He liked the Doors; she liked the Beatles. Neither was flexible. She became pregnant with me to keep my father at home. When that didn’t work, she had an affair. He kicked her out of our house and our lives. (I didn’t meet her until I was 24, a story for another time.)

The woman my father should have married, a lovely artist named Angela, was brushed aside after my father met the woman who would become my stepmother for two decades. She was a bleach-blond hourglass and 10 years his junior. She quit high school, moved in and they got married. She cheated on my father during the first year of marriage, and though he stayed married to her, he later told me “I never forgave her.”

By age nine, I loathed my stepmother. That was the year I came to new awareness. She had borrowed five dollars from me and promised to pay it back. Days later, when we were at the store and I wanted to buy a toy, I asked for my money back. She said, “I took you to McDonald’s today. So, I figure I paid you back.” I stared at her in disbelief. What? Food is not cash. I want my goddamned money to buy a Magic Eight Ball.

Over the next 20 years, she cheated more, beat my brothers and me, called us names, picked my father’s pockets, and flew into rages for little more than a drop of food on her “nice clean floor.” And then, sometimes, during movies like Sound of Music, Oliver, and Terms of Endearment, she would sit on the couch, and weep like a little girl. She was a puzzle. In 1998, my father divorced my stepmother and when he called to tell me, I danced through my kitchen singing, “Happy days are here again.”

My father, bless his soul, had what one of his brother’s called, “Broken wing syndrome.” He liked to save the damsels in distress. Angela didn’t need saving. I am guessing my mother and stepmother did. Although you can see it as an altruistic method of operation, if you’ve ever tried to save someone, you know it just doesn’t work. If you’re lucky enough to find one person to love who supports you and you support them, hang on tight. When I shake the Magic Eight Ball and ask, “Will I find my prince?” It says, Ask again later.

David Spade once said that when you grow up poor you don’t know it until someone else tells you. For the first few years of my life, my father, my brother Tony, and I lived in a couple of rented houses before being evicted because my father was in his 20s and liked to party. We finally settled in an apartment and were on food stamps, although my father never told me until I was in my 20s.

My brother and I went to work with my father almost every day (he owned a shoe-repair business) until we started school. Sometimes we had babysitters, and sometimes my father dated women so there would be someone to take care of us. Unfortunately, some of these women stole his record albums and never came back.

When I was four, my father met a 16 year-old-girl named Vickie who was happy to quit high school and move in with us. (that is another blog by the way) Vickie kept my brother and me clean, fed, and had us in bed every night by nine. She also beat us when my father wasn’t around and insisted we call her Mom.

My father married Vickie two years later and bought us a house. The place was crap brown with a wrap-around porch, a rotting roof, and black windows. My brother and I cried the day we moved in. Over the next two years, although my father spent a lot of money and time to have our “haunted house” remodeled, I still sensed it was shoddy compared to the other houses on the street with their Ionic pillars, manicured shrubs, and intact families. When friends visited, they said, “Oh, your house is nice on the inside.”

When I was nine, my father moved my brother and me out of public school and into Catholic school. We had not been baptized and I only heard “god” when my stepmother said, “You goddamned kids.” Because we wore uniforms, it was easy to blend in. And I was never the kind of girl who could look at people’s shoes and know how much money their parents made.

In middle school, we no longer wore uniforms, and my stepmother bought my clothes (polyester pants, blouses) at J.C. Penney and Sears, which felt normal. One day, the Queen Bee walked over to me, felt the material of my blouse, and said, “Where did you get this?” I said, “Sears.” She smirked, and said, “Ohhh.” I think it was then that I knew. Some of my friends wore Aignier and L.L. Bean. I had never heard of either.

Over the next year, after I noticed the Queen Bee and her cohort wore Izod Lacoste polos, which I saw as a symbol of wealth and status, I became obsessed with getting a shirt of my own. So, my stepgrandmother took me to the outlet mall and bought me two Izod polos. I couldn’t wait to show the rich kids I was not a loser.

Of course, now I know those Izods were like me–slightly irregular. And even though my stepgrandmother bought me designer jeans and name brand clothes, I never really fit in with the Queen Bee and her friends. They played tennis and golf, and I ran track. Their parents had cocktail parties, my father went bowling.

Growing up poor taught me humility. Sometimes I think my life has been one “character building” event after another. I know the value of a dollar and love to do hard work. The things I hold dear, after family, dogs, and friends, are the sentimental gifts I have received over the years–books, toys from my childhood, love letters. I have no idea what it’s like to grow up rich, or be rich, however, I imagine it feels as though you can never have enough.

In the ’80s, when I was coming of age, MTV was everything–I loved the thrift-store fashions of Cyndi Lauper, the fluffy skirts, zip up boots, and torn stockings. She looked so cool. But I went to a catholic school where we had to follow a dress code: blouses, slacks and/or skirts (not too far above the knee), no stirrup pants, and dress shoes. The most rebellious I could get was popping my collar.

I had grown up as a tomboy, two years younger than my brother, and because we were not rich, my father dressed me in “Tony’s” hand-me-downs. Until I was about five, I believed I was a boy. My father let me walk around the house with no shirt on, Tony and I had fist-fights with kids on the playground, and I only wore pants.

My father remarried when I was six, and my stepmother introduced me to a hairbrush, ruffled panties, dresses, tights, and patent leather shoes. It was not a smooth transition. When she brushed my knotted hair, I wailed and she yelled. And when I hung upside down from a tree limb while wearing a dress, consequently showing my flowered underwear, she told me to get down.

Looking back, I realize my stepmother was a trend follower. She wore T-shirts with sayings on them, high-priced designer jeans, and used top-of-the-line makeup and hair products. She bought school clothes for my brother and me at the very uncool Sears store in the mall and sneakers from a place called Philadelphia Sales. Cheap!

Of course, in high school, I was desperate to fit in and begged my stepmother to buy me Izod polos, designer jeans, and elf boots. She took me to outlet malls where they had “slightly damaged” Izod clothing and I got my polos. I borrowed elf boots from my friend, and was grateful for being a cheerleader who got to look cool in my uniform on game days.

Luckily, my stepgrandmother bought me Forenza sweaters and wide wale corduroys from the Limited, and Gloria Vanderbilt designer jeans. And for my senior prom, my father gave me an unlimited price tag to buy any dress I wanted–a mauve Southern Belle dress and finger-less gloves.

One of the things I liked about 80s fashions were they were influenced by the late 50s and early 60s fashions–saddle shoes, penny loafers, poodle skirts and angora sweaters worn over a blouse with a Peter Pan collar. When the GoGos appeared on MTV with their short hair styles and blouses, my father thought they were a 50s band.

As a woman who will turn 50 this year (yay!) I wear what I like to call “classic” fashions. Collared blouses, slacks, and shoes that don’t go out of style. This is not necessarily to make a statement; I think it’s because growing up poor taught me to be thrifty. I want my clothes and shoes to last. I shop at Goodwill and second-hand stores. I visit Nordstrom Rack, not Nordstrom. And if I think a piece of clothing I buy won’t last at least a decade, I usually put it back on the rack.

Some people always seem to know which trends are coming. The messy bun, big sunglasses, eyelash extensions, yoga pants. If it weren’t for my grown daughters, I might never know what was “in style.” I work in a professional office, so I wear dress clothes, but I feel like a nerd in disguise. I’ll leave the trends to the people who have the time and energy to follow them.

I’m deeply grateful that my father dressed me in boys’ clothes. I know I will never be a princess. Today I’m wearing a pair of Doc Marten saddle shoes I bought at a second-hand store for $35. I love telling people how inexpensive they were. I get many compliments on them. I once got a snide comment, but that woman and I hardly talk anymore.

My father opened a shoe-repair business when I was two, and I spent a lot of time around adults. There was Joyce, the woman who made tie-dyes and sewed leather; Bob, my father’s buddy who fixed shoes; and the array of business men (it was the 70s and they were mostly men) who wore fedoras and suit jackets, and called me Chooch. Spending time around adults helped me cultivate a decent b.s. detector.

My memories from this period, before age four, are idyllic. My father had divorced my and my brother’s mother, and the three of us lived in a modest apartment. We were poor in money but rich in love, and we went everywhere together–the shoe-repair shop, the bowling alley, the bar. We ate TV dinners in front of the black and white console, mostly Laugh-In and The Sonny and Cher Show, or scarfed fried clam strips down the street at Sharkey’s Tavern.

After my father started dating “Vickie,” a high-school dropout with wavy bleached hair and freckles, my life changed. Although Vickie dressed my brother and me in nice clothes, and kept us clean, she also whipped us with leather belts and called us names. Her brother molested me when I was four. And, Vickie was a serial cheater. My father married her in 1975, and six months later my younger brother was born. He caught Vickie the first time when my brother was less than one.

My father and Vickie stayed together for 23 years. Living with her until I was 18 (I moved out on my birthday) taught me injustice, to keep silent, and to cower in the presence of a bully. Her brother had said to me, “Don’t tell your daddy what we did. He’ll think you’re nasty.” Vickie said to me, “If you tell your father I hit you, you’ll get it worse.” And when I told other family members or adults about what was happening in our home, I got a pat on the head, and a, “Oh, you’re just being dramatic.”

It may not surprise you that when I married, I fell for a male version of Vickie and left my relationship. More than once. Several people waved warning flags in my face, which I ignored. It wasn’t until the love of my life divorced me that I saw I was the problem. It took ten months for me to see through my male Vickie’s bullshit. Now, I’m single and am trying to make up for my mistakes through reading, self-reflection and therapy.

My father divorced Vickie in 1998, and he passed away in 2012. Vickie remarried and from what I hear, is cheating. I wish she would have sought help for whatever childhood haunts keep her in that self-destructive cycle. To make matters worse, I now have a good friend who’s been hoodwinked by his own version of Vickie. Did I warn him? Yup. Did he yell at me and cast me aside? Yup. It’s as if I’m reliving my childhood, watching my friend instead of my father, heading for a fall.

My hope for my friend, who usually has a keen bullshit dectector, is that he will wake up before too much damage has been done. But, similar to Vickie, his enchantress is pretty, fit, and an amazing liar. Friends tell me, “Don’t worry. She’ll hang herself. And then you can say, ‘I told you so.'” Problem is, I’m not going to say I told you so. I’m going to be there for my friend if he feels had can confide in me. Keep your fingers crossed.