Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

I’ve been thinking a lot about responsibility over the past couple of days. For as long as I can remember, I have felt “responsible” for other people’s feelings — their happiness, anger, sadness, hunger, well-being, etc., etc. Some of it, I believe, comes from being an older sibling. I was seven when my brother Jack was born, and from the moment I saw his pursed lips and downy hair, inhaled the baby scent from the top of his head, I wanted to protect him. It was both understood and stated, with my father’s tireless refrain: “Watch your brother. Watch your brother. Watch your brother.” I adored Jack, and enjoyed feeding him, changing his diapers, and cuddling with him on the couch.

The responsibility thing really hit home during Christmas 1977. I brought home an ornament I’d made at school: green construction paper, red yarn, and silver glitter. Although I don’t remember, I must have left it on the dining room table where my stepmother was displaying all of her Princess House crystal. I was at school when Jack pulled on the table cloth and hundreds of dollars of crystal crashed to the floor. When I arrived home that evening, my stepmother screamed and screamed. Since Jack was only a toddler, and was trying to get my ornament, the broken crystal was all my fault.

Years later, when I started dating, I took responsibility for the feelings of my boyfriends, and anyone else who came along. If X had a bad day, it was up to me to cook him a nice meal and let him relax so he cheered up. If X wanted to go to dinner, I chose the restaurant, and if he disliked the meal it was because I had made a bad choice. If X’s family didn’t like me, it was because I was too sensitive and analytical, so I tried really hard to be amazing and wonderful.

Most recently, I’ve been reflecting on how I felt responsible for my father’s happiness. His wife was an incurable cheater, and I never told him, until 1988, when he received an anonymous letter saying “Your wife is sleeping with my brother. He’s married and has five kids.” My father confronted my stepmother, and of course, she said it wasn’t true. So, he hid a tape recorder in his bedroom. Confronted with the evidence, she said, “How dare you spy on me.”

My stepmother was a special kind of crazy, both unpredictable and prone to violent outbursts, the kind of crazy I couldn’t manage as a 20 year old. But, I figured since my father had confided in me, and was planning to divorce her, I should take him out for a drink and spill my guts. We went to the No. 5 in Binghamton, New York, and drank late into the evening. I told him everything I knew about her cheating, starting from when I was four until the present day. My father showed no emotion. The following day, he filed divorce papers and sent them to his mother in law’s house where his wife was staying.

A couple of weeks later, my father invited me to dinner at his house with Jack. On the drive over, he said, “I’m gonna take her back.” I started bawling. All those stories! All of her lies! “How could you?” I asked. My father said when he brought over the papers, she fell to the floor and started kissing his feet. She promised over and over to stay faithful. “I don’t approve,” I said. “But you’re a grown man.” He smiled, and answered, “You’re absolutely right. You’re so protective. Just like grandpa.” Damn straight.

There have a been a couple more times in my adult life where I have had the opportunity to let a person I care about know they were being cheated on. Both times, after telling, it blew up in my face. So, if you’re keeping track, that’s three strikes. I’m out.

It really sucks to see someone you love getting hurt by someone else simply because they are a good liar. However, if you out a cheater, that falls right in line with shooting the messenger. You’re going to get hurt unless the person you tell has an enormous amount of self awareness, and believes you, not the cheater. At the same time, if you’re like me and have a visceral reaction to seeing your loved ones getting screwed over, perhaps you can explore those feelings in a blog post.

P.S. My father and his wife renewed their wedding vows in 1988, moved to Florida the following year, and bought a business. Ten years later, he filed for divorce and they went through an acrimonious process. My father moved back to Binghamton.

Back in the summer of 2009 I started seeing a therapist because my childhood haunts were interfering in my eight-year marriage in a very real way. I was blissfully married, and I was afraid I was about to destroy everything. But why?

My therapist “Bruce” was (and is) one of the coolest people I’ve ever met. His face is careworn, and his hair hangs to his shoulders in thin white strands. He looked sort of like Bill Murray, and we joked about how much we loved the movie What About Bob?

Bruce was old enough to have been in practice during the I’m OK; You’re OK phenomenom of the 1970s. However, Bruce developed his own version of the mantra: “I’m fucked up; you’re fucked up.” That saying felt so much more real and relatable. And, after I left my sessions with Bruce, I felt sane and normal.

Bruce and I discussed childhood abuse of all types, and the lingering effects. I was sure those “effects” were leading me to think Eric was going to dump me. Other than his being extemely introverted and pensive, there were no real signs. And with the gift of hindsight, it may have been better to talk to Eric instead of the therapist.

Regardless, another topic Bruce and I talked about was breaking the cycle of abuse. He said the statistics show only about 1 in 5 people is able to succeed. I wondered about myself. By this time, I had a 17-year-old daughter, a 13-year-old daughter, and 4-year-old son. I had given them spankings on occasion, and did my fair share of yelling. But abuse?

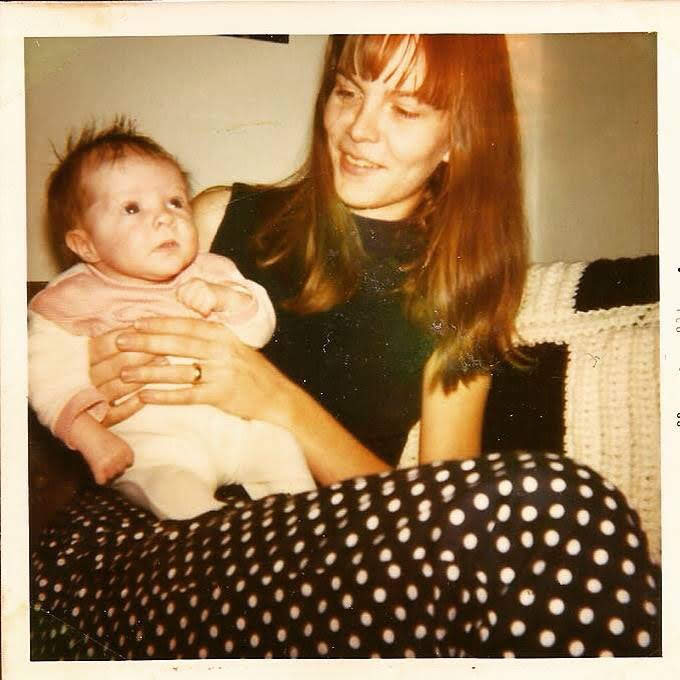

When I had my first baby, Jessica, she was so beautiful and precious with the most perfect little fingers, I could NEVER imagine hurting her. Her father and I agreed there would be no spankings. Then he left to serve on a navy meteorological team in Japan, and I stayed state-side with his parents and Jessica.

After Jessica learned to walk, like most toddlers, she ventured around and got into things she shouldn’t touch. One day, I tried repeatedly to keep her from sticking her hand into the kitchen garbage. After numerous unsuccessful attempts, I took her right hand and lightly slapped it. She started crying. My chest ached, but she never touched the garbage again.

When compared to the “spankings” I received as a kid, I would say my kids got off easy. I never used any weapons, like leather belts, wooden spoons, or knuckles or diamond rings to the head. Slaps across the face were also a no-no. I’m aware people have strong opinions about physically punishing children, and as for me, because of the severity of the beatings my brothers and I endured, I dislike anyone hurting someone smaller and weaker than they are.

Now that my daughters are grown, they blast me for being a fiery-tempered smart mouth when they were young more than inflicting physical punishments. I was 23 when Jessica was born. I divorced her father when she was two. I remarried when Jessica was four. Nine months after that wedding Josie was born. Then her father died when she was 18 months old. That’s a lot of chaos for two young girls and one woman to endure.

Although I’m resilient and loving, I am also brutally honest–like my father. He wasn’t always tactful, and he sometimes called me names like “goddamned dummy” or “nutcase.” At the same time, he was slow to anger. So, if he punished me physically, I had to have done something really wrong, like when I accidentally set a fire behind the Vestal Plaza in New York and got the belt. That only happened once.

There are definitely times I have snapped at the girls, yelled, or made a huge deal out of nothing. And, when I catch myself sounding like the icy voice of my former stepmother, I clam up. Fortunately, I apologize to my daughters when I’ve done something wrong. With my son, it’s so different. I was 36 when he was born, and although I’d like to say I have mellowed, to be honest, I was just plain tired.

My son was wild as a toddler. He had blond curly hair and a crooked smile. When he ran out onto the volleyball court midgame, then turned and grinned at me I wanted to thrash him. But he was so freaking cute, how could I? When his father and I eventually separated (my prediction of wrecking the marriage came true), Vinny was five.

Now, Vinny is a chill teenager. I couldn’t tell you the last time I spanked him or yelled at him. And over the past 18 months, with his sisters out of the house, and his father extremely busy with his new life, my son and I have spent an enormous amount of time together. We spent 8 days in New York, took two roads trips to Portland, OR, and many road trips to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. In the car, we don’t listen to music; we talk. We talk about anything and everything. No subject is forbidden.

In my childhood home, there was no talking about feelings, no apologizing. There was no, “How was your day?” or “Do you want to talk about something?” When I watched the Brady Bunch, I was so envious when the mom or dad knocked on the kids’ door and asked to talk. Especially since there was a character named “Cindy.” If only my parents had come into my room with a soft voice, and said, “Cindy. Are you okay?”

One of my favorite things about my relationship with my kids is our inability to keep secrets. I have always talked to them as if they were adults in training (because they are). And, as much as I loathe when they gang up on me, make fun of me for mispronouncing current band names or rappers, or pointedly argue with me — that is how their father(s) and I raised them. They need to advocate for themselves even if it pisses someone off.

My oldest daughter once said I was too easy on her growing up. My middle daughter says I was abusive. My son may be too young to look at me reflectively, but right now, we are as close as siblings. There are three things I have taken away from my father’s parenting: 1. Never be afraid to act silly in front of and with your kids. The humility will go a long way. 2. Tell the truth. 3. Don’t be afraid to apologize for your bad behavior. In that way, you teach forgiveness. I had to learn that one in spite of my father. I’m fucked up; he’s fucked up. We’re all works in progress, eh?

My mother, Carla Bosch, was born in 1946 in a displaced persons’ camp in Bucholtz, West Germany. Her father was loving; her mother was cruel. After WWII they moved to Amsterdam, Holland, where they lived until my mother was 11. Then they moved to the states. The school district bumped her up two grades. I know little about her life during her teen years except that her mother constantly called her “ugly,” and if she showed signs of angst, her mother checked her into the psych ward at the local hospital.

In 1965, my father and mother met in a pizza parlor in Binghamton, New York. She said he looked like Woody Allen with black hair. They started dating and within several months, she became pregnant with my brother Tony. My parents married in Nov. 1965, spent their honeymoon in Cooperstown. Then they moved into a rented house on the south side of Binghamton. Tony Jr. was born in May 1966, and slept in a toy chest. My parents paid for diapers by hustling pool at local taverns.

My father doted on my brother, however, he was not a man easily tamed. He believed women stayed home, and men went out partying. In an attempt to keep him out of the bars, my mother became pregnant with me. No matter how cute I was, and I was cute, her plan failed. She started leaving my brother and me with sitters, and according to gossip, sometimes alone. When I was six months old, my father kicked her out of our house, filed for divorce, and took full custody of my brother and me. He told her never to contact us again.

Growing up, Tony and I were not allowed to talk about “Carla” in front of my stepmother who insisted we call her “Mom.” And if I asked my father’s family about my birth mother, they said, “She left you. You don’t want to know her.” But I did. There were only about five photos of her in the entire house. I studied her high cheekbones, green eyes and square chin. Did she ever think about us? Where did she live? And when I walked around town, every woman I saw was a possibility. Is that her? Is that her?

As I came of age, I tried to make peace with not knowing my mother. Tony always said, “Don’t bug Dad with your questions.” But, Tony was three when she left! Surely he had some memory of her. He said he remembered her throwing a plate. And that she taught him to read. But I had zero. Not a voice. Not a scent. Not an image. I stored a few memories of the women my father dated before he married my stepmother.

After I graduated from high school, Tony was killed in a motorcycle accident. That cemented my dislike of my stepmother. In 1989, I joined the navy. Perhaps, I thought, if I “traveled the world,” I might eventually find our mother. In 1992, while stationed in Monterey, California, I became pregnant. The doctor asked, “Did your mother take drugs when she was pregnant with you?” I said I didn’t know. He said, “Can’t you ask her?” I shook my head and waited until I got into my car before I cried.

One night while I was nursing my daughter “Jessica” and watching the news, a segment called Finder on the Money explained “How to find a long-lost relative.” I took down the number. They put me in touch with a private investigator. And though I knew my mother’s name, birth date, and birth place, he said he needed her social security number.

I ordered my birth certificate, and my parents’ social security numbers were on it! Within a couple of days, the investigator called with my mother’s address in Newport, Rhode Island. I drafted a letter. “Hi, Mom. It’s me. Your daughter Cynthia. Do you want to know me?” Then I bought a pack of Marlboro Reds and chain-smoked while waiting for her response.

In her very first letter she asked me to imagine being a 21-year-old mother, pregnant with her second child, surrounded by the tumult of the late 1960s–the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The Vietman War. And then she asked, “Does your brother want to know me?” I had to write back and tell her Tony was dead. She sent back a short note: “How tragic. I broke my glasses. More later.” I can’t imagine the guilt she must have felt — leaving us behind — knowing she would never see Tony again.

Several months later, my mother and I made plans to meet in Binghamton. I was 24. She had gotten remarried the year my brother was killed and was bringing her husband Bill. I had to keep the entire thing secret from family, because my father would not be happy. (A friend dropped the dime on me, and I got an earful from my dad. See earlier post–Secrets Cause Cancer.)

My mother and I met at a restaurant that no longer exists. It was encased in glass, and I saw her before she could see me. I looked in and waved, and she got up from the table to greet me. My mother is 5 foot 11, with salt and pepper hair cut in a bob. She wore a linen blazer and long skirt. She leaned over and gave me a half hug, then invited me to sit with her and Bill. He stood to shake my hand. He had black hair and glasses, and an inviting smile.

The dinner conversation was superficial. With Bill there, I was hardly interested in poking into my mother’s reasons for leaving. However, when he left the table, she said she was sorry she left. I didn’t quite know how to respond, except to say Thank you. One thing I did appreciate was that my mother wore silver jewelry, which was also my favorite. At the end of the dinner, I went to where I was staying. The next day, before they left town, my mother and Bill stopped by to meet Jessica. And then they were gone.

Now, my mother and I are pen pals. She does not have a computer. She does not have a cell phone. She will never travel to Idaho. I send her a birthday card every August, and an Enjoy Your Day card in May. At this point, we will never be best friends. However, I am glad I got to meet her. My father made his peace with it as well. I’m hoping someday we meet again, but I have no idea how that might happen.

My mother and father split up when I was six months old, so my experience with the broken family started early. My first memories include my father, my older brother Tony, and many members of my large extended family. We are Italian-Americans from upstate New York, and except for mafia ties, we live up to the copious stereotypes: loud, romantic, passionate, beautiful, dramatic.

In 1975, my father remarried. I was six and Tony was eight. It was a different time, and we were not invited to the wedding or reception. In fact, Tony stayed with a friend, and I stayed with a friend of my stepmother’s. And although I don’t remember the woman’s name, I do remember playing the piano, and incorporating “turd” into an impromptu song. She yelled, “Hey! We don’t use that kind of language in this house.”

Six months after the wedding, my father bought us a house on the west side of Binghamton. My stepmother was 19, Tony was 9, and I was 7. My baby brother was 9 months old. We were told he was a “preemie” — but he weighed six pounds, six ounces at birth. You do the math.

Tony and I started at a new school. Although I wasn’t sure how we were different from other families, I knew we were different. My father was a shoe-repair man who owned a cobbler shop. Instead of wearing a suit to work, he wore denim and leather. My stepmother was a stay-at-home mother who wore no bra beneath her T-shirts, had Farrah Fawcett hair, and marble blue eyes. One of the young men in our neighborhood asked her out.

Mine was not a peaceful childhood. There was a lot of fighting between my father and stepmother about Tony and me. She was intensely jealous of anyone stealing attention from her. She was a screamer. My father was slow to anger, but once he broke, look out. And while he was not quick with the belt, she was. Any small thing could set her off–pots and pans “shoved half-assed in the cupboards,” food splattered on the floor, a crass remark. And she hit in public.

Tony started running away from home at age 14. I hid in my bedroom with books, TeenBeat, and sketchpads. My younger brother was beaten so often that when I reached to touch him, he ducked. When my father was home, my stepmother never yelled or hit us, and spoke with a sickeningly sweet voice. When my father was gone, she was a ticking bomb ready to go off at the occurrence of spilt milk. To this day, when I meet a person who reminds me of my stepmother, my antennae lift in response. And I have a sincere distrust of people who bully children. A therapist I saw for a while told me, “You have strong feelers for a reason. Trust them.”

In 1998, my father divorced this wife, after two decades of her infidelity, fighting, and confession that she stuck around for the money. One day I asked him, “Why did you stay so long?” He shook his head. “Ah. When you and Tony were small, whenever I saw your messy hair and dirty faces, it broke my heart. I wanted you to have a mother.”

The decisions we make out of love, or what we think is love, are often ill-fated. Self-delusion has to be one of the most powerful tools of the mind. Think here of the spouse of the serial killer who says, “I never knew.”

My first pregnancy and marriage was at age 23. It took me less than two years to rip that apart and create what I loathed–a broken family–all because some guy said I was his true love. Luckily, my ex-husband Jeremy is not a grudge holder, and we are still friends. God bless that guy.

Something about turning 50 has made my brain go wonky. I keep having dreams about my two ex-husbands, and my late husband, and I spend a lot of time wishing I had done things differently. Perhaps made decisions based on logic instead of “love.” Regret, coulda, shoulda, woulda, etc. Because of childhood abuse, I have been in therapy most of my adult life, and I am still working through a lot of the muck.

The therapist I’m seeing now is helping me connect the pain of my current heartbreak over losing Eric and the chance to rebuild our family with the lingering issues from my childhood. It’s a scary process, however, I’m determined to reach a place of peace and happiness. It’s easier to run away–drink, have sex, ignore your kids, and pretend everything is great. But at this point, I’m way more interested in doing the hard work if that’s what it takes to become unbroken.

In 1997, I was a junior in Humanities at Lewis-Clark State College in Lewiston, Idaho. The journalism program was defunct, and since I had just become a 27-year-old widow with two young daughters, I switched to creative writing and enrolled in my first creative nonfiction class. I just wanted to learn how to write.

I wrote my first nonfiction piece when I was about five. It was a typed paragraph, and the paper I used ended up with a small coffee stain in the right corner. The text read something like, “I asked my father for money, but because we don’t have a lot, he said no. But at least I have a new mother, and I love her!!!!!” My father found and folded the letter, and hid it in his safe for years. In 1989, when I was in the navy, he sent me the letter with a sticky note that said, “I hope you still feel the same.”

At age 20, I did not feel the same. As a matter for fact, after my beloved older brother Tony was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1987, my father turned to his wife not me, to grieve. I blamed his wife for Tony’s death. She had been an abusive monster when we were growing up. My brother turned to drinking and drugs, I turned to men. The night my brother died, my grief trickled out into absolute hatred for my stepmother.

I mention the letter because it shows how long I’ve been in love with writing “the truth.” As I came of age, even when I wrote fiction, I used the first person “I” and described events from my actual life. Write what you know they say. As a teenager, I knew blackheads, bullying, and boys. If my stepmother had ever caught me writing negative things about her, she would have shown them to my father and I would have been punished. I was the “big mouth” who complained all the time.

When I was 13, a woman I babysat for gave me the memoir Mommie Dearest by Christina Crawford, actress Joan Crawford’s adopted daughter. My life was never the same. Mommie Dearest is an expose on child abuse. Christina’s biological mother had given her up (just as mine did) and she was being beaten, ridiculed, and shamed by her “new” mother. I had no idea that other kids suffered abuse. No one at school EVER talked about it, and when I told Tony our stepmother was mean,” he said, “Shut up. Dad doesn’t need to hear that shit.”

By the time I was in college, and had gone on to graduate school, writing my “truth” left some of my colleagues unsettled. “How can you write such nasty things about your family?” they asked. I wrote the truth, nasty or not. And since my father had divorced my stepmother in 1998 and she lived 3000 miles away, I felt somewhat safe. Writing about people who hurt us is no new debate. If you’ve read This Boy’s Life, The Liar’s Club, Hungry for the World, or Mommie Dearest, imagine the criticism those authors faced.

If anyone cares to know, writing nonfiction for me is telling the truth of my experience to the best of my memory. My father once paid me an enormous compliment after reading my work, and I keep that in mind when I write. He said, “I remember it differently, but those are your memories.” For a man with a high school education and shoe-repair man’s apprenticeship, I thought he sounded damned professorial.

And speaking of professors, my first writing teacher, who is also a dear friend and mentor, once said, “No one is all evil or all good. You have to show them as a rounded human being.” Believe it or not, rounding out my stepmother is not that difficult. Writing about my brother Tony, however, whom I worshipped until the day he died, that’s a whole other story. I was his patsy, his sidekick, Laurel to his Hardy. One day, I may sit down and write the truth of our story. But I’m still working on it —

My father was not the best at picking women. My biological mother who was “the most beautiful woman he had ever seen” became pregnant several months into their dating. They married, had my older brother, and fought all the time. I’ve heard both sides of the story and my interpretation is this: My father was a good-time Charlie, and my mother was a feminist. He liked the Doors; she liked the Beatles. Neither was flexible. She became pregnant with me to keep my father at home. When that didn’t work, she had an affair. He kicked her out of our house and our lives. (I didn’t meet her until I was 24, a story for another time.)

The woman my father should have married, a lovely artist named Angela, was brushed aside after my father met the woman who would become my stepmother for two decades. She was a bleach-blond hourglass and 10 years his junior. She quit high school, moved in and they got married. She cheated on my father during the first year of marriage, and though he stayed married to her, he later told me “I never forgave her.”

By age nine, I loathed my stepmother. That was the year I came to new awareness. She had borrowed five dollars from me and promised to pay it back. Days later, when we were at the store and I wanted to buy a toy, I asked for my money back. She said, “I took you to McDonald’s today. So, I figure I paid you back.” I stared at her in disbelief. What? Food is not cash. I want my goddamned money to buy a Magic Eight Ball.

Over the next 20 years, she cheated more, beat my brothers and me, called us names, picked my father’s pockets, and flew into rages for little more than a drop of food on her “nice clean floor.” And then, sometimes, during movies like Sound of Music, Oliver, and Terms of Endearment, she would sit on the couch, and weep like a little girl. She was a puzzle. In 1998, my father divorced my stepmother and when he called to tell me, I danced through my kitchen singing, “Happy days are here again.”

My father, bless his soul, had what one of his brother’s called, “Broken wing syndrome.” He liked to save the damsels in distress. Angela didn’t need saving. I am guessing my mother and stepmother did. Although you can see it as an altruistic method of operation, if you’ve ever tried to save someone, you know it just doesn’t work. If you’re lucky enough to find one person to love who supports you and you support them, hang on tight. When I shake the Magic Eight Ball and ask, “Will I find my prince?” It says, Ask again later.

David Spade once said that when you grow up poor you don’t know it until someone else tells you. For the first few years of my life, my father, my brother Tony, and I lived in a couple of rented houses before being evicted because my father was in his 20s and liked to party. We finally settled in an apartment and were on food stamps, although my father never told me until I was in my 20s.

My brother and I went to work with my father almost every day (he owned a shoe-repair business) until we started school. Sometimes we had babysitters, and sometimes my father dated women so there would be someone to take care of us. Unfortunately, some of these women stole his record albums and never came back.

When I was four, my father met a 16 year-old-girl named Vickie who was happy to quit high school and move in with us. (that is another blog by the way) Vickie kept my brother and me clean, fed, and had us in bed every night by nine. She also beat us when my father wasn’t around and insisted we call her Mom.

My father married Vickie two years later and bought us a house. The place was crap brown with a wrap-around porch, a rotting roof, and black windows. My brother and I cried the day we moved in. Over the next two years, although my father spent a lot of money and time to have our “haunted house” remodeled, I still sensed it was shoddy compared to the other houses on the street with their Ionic pillars, manicured shrubs, and intact families. When friends visited, they said, “Oh, your house is nice on the inside.”

When I was nine, my father moved my brother and me out of public school and into Catholic school. We had not been baptized and I only heard “god” when my stepmother said, “You goddamned kids.” Because we wore uniforms, it was easy to blend in. And I was never the kind of girl who could look at people’s shoes and know how much money their parents made.

In middle school, we no longer wore uniforms, and my stepmother bought my clothes (polyester pants, blouses) at J.C. Penney and Sears, which felt normal. One day, the Queen Bee walked over to me, felt the material of my blouse, and said, “Where did you get this?” I said, “Sears.” She smirked, and said, “Ohhh.” I think it was then that I knew. Some of my friends wore Aignier and L.L. Bean. I had never heard of either.

Over the next year, after I noticed the Queen Bee and her cohort wore Izod Lacoste polos, which I saw as a symbol of wealth and status, I became obsessed with getting a shirt of my own. So, my stepgrandmother took me to the outlet mall and bought me two Izod polos. I couldn’t wait to show the rich kids I was not a loser.

Of course, now I know those Izods were like me–slightly irregular. And even though my stepgrandmother bought me designer jeans and name brand clothes, I never really fit in with the Queen Bee and her friends. They played tennis and golf, and I ran track. Their parents had cocktail parties, my father went bowling.

Growing up poor taught me humility. Sometimes I think my life has been one “character building” event after another. I know the value of a dollar and love to do hard work. The things I hold dear, after family, dogs, and friends, are the sentimental gifts I have received over the years–books, toys from my childhood, love letters. I have no idea what it’s like to grow up rich, or be rich, however, I imagine it feels as though you can never have enough.

In the ’80s, when I was coming of age, MTV was everything–I loved the thrift-store fashions of Cyndi Lauper, the fluffy skirts, zip up boots, and torn stockings. She looked so cool. But I went to a catholic school where we had to follow a dress code: blouses, slacks and/or skirts (not too far above the knee), no stirrup pants, and dress shoes. The most rebellious I could get was popping my collar.

I had grown up as a tomboy, two years younger than my brother, and because we were not rich, my father dressed me in “Tony’s” hand-me-downs. Until I was about five, I believed I was a boy. My father let me walk around the house with no shirt on, Tony and I had fist-fights with kids on the playground, and I only wore pants.

My father remarried when I was six, and my stepmother introduced me to a hairbrush, ruffled panties, dresses, tights, and patent leather shoes. It was not a smooth transition. When she brushed my knotted hair, I wailed and she yelled. And when I hung upside down from a tree limb while wearing a dress, consequently showing my flowered underwear, she told me to get down.

Looking back, I realize my stepmother was a trend follower. She wore T-shirts with sayings on them, high-priced designer jeans, and used top-of-the-line makeup and hair products. She bought school clothes for my brother and me at the very uncool Sears store in the mall and sneakers from a place called Philadelphia Sales. Cheap!

Of course, in high school, I was desperate to fit in and begged my stepmother to buy me Izod polos, designer jeans, and elf boots. She took me to outlet malls where they had “slightly damaged” Izod clothing and I got my polos. I borrowed elf boots from my friend, and was grateful for being a cheerleader who got to look cool in my uniform on game days.

Luckily, my stepgrandmother bought me Forenza sweaters and wide wale corduroys from the Limited, and Gloria Vanderbilt designer jeans. And for my senior prom, my father gave me an unlimited price tag to buy any dress I wanted–a mauve Southern Belle dress and finger-less gloves.

One of the things I liked about 80s fashions were they were influenced by the late 50s and early 60s fashions–saddle shoes, penny loafers, poodle skirts and angora sweaters worn over a blouse with a Peter Pan collar. When the GoGos appeared on MTV with their short hair styles and blouses, my father thought they were a 50s band.

As a woman who will turn 50 this year (yay!) I wear what I like to call “classic” fashions. Collared blouses, slacks, and shoes that don’t go out of style. This is not necessarily to make a statement; I think it’s because growing up poor taught me to be thrifty. I want my clothes and shoes to last. I shop at Goodwill and second-hand stores. I visit Nordstrom Rack, not Nordstrom. And if I think a piece of clothing I buy won’t last at least a decade, I usually put it back on the rack.

Some people always seem to know which trends are coming. The messy bun, big sunglasses, eyelash extensions, yoga pants. If it weren’t for my grown daughters, I might never know what was “in style.” I work in a professional office, so I wear dress clothes, but I feel like a nerd in disguise. I’ll leave the trends to the people who have the time and energy to follow them.

I’m deeply grateful that my father dressed me in boys’ clothes. I know I will never be a princess. Today I’m wearing a pair of Doc Marten saddle shoes I bought at a second-hand store for $35. I love telling people how inexpensive they were. I get many compliments on them. I once got a snide comment, but that woman and I hardly talk anymore.

My father opened a shoe-repair business when I was two, and I spent a lot of time around adults. There was Joyce, the woman who made tie-dyes and sewed leather; Bob, my father’s buddy who fixed shoes; and the array of business men (it was the 70s and they were mostly men) who wore fedoras and suit jackets, and called me Chooch. Spending time around adults helped me cultivate a decent b.s. detector.

My memories from this period, before age four, are idyllic. My father had divorced my and my brother’s mother, and the three of us lived in a modest apartment. We were poor in money but rich in love, and we went everywhere together–the shoe-repair shop, the bowling alley, the bar. We ate TV dinners in front of the black and white console, mostly Laugh-In and The Sonny and Cher Show, or scarfed fried clam strips down the street at Sharkey’s Tavern.

After my father started dating “Vickie,” a high-school dropout with wavy bleached hair and freckles, my life changed. Although Vickie dressed my brother and me in nice clothes, and kept us clean, she also whipped us with leather belts and called us names. Her brother molested me when I was four. And, Vickie was a serial cheater. My father married her in 1975, and six months later my younger brother was born. He caught Vickie the first time when my brother was less than one.

My father and Vickie stayed together for 23 years. Living with her until I was 18 (I moved out on my birthday) taught me injustice, to keep silent, and to cower in the presence of a bully. Her brother had said to me, “Don’t tell your daddy what we did. He’ll think you’re nasty.” Vickie said to me, “If you tell your father I hit you, you’ll get it worse.” And when I told other family members or adults about what was happening in our home, I got a pat on the head, and a, “Oh, you’re just being dramatic.”

It may not surprise you that when I married, I fell for a male version of Vickie and left my relationship. More than once. Several people waved warning flags in my face, which I ignored. It wasn’t until the love of my life divorced me that I saw I was the problem. It took ten months for me to see through my male Vickie’s bullshit. Now, I’m single and am trying to make up for my mistakes through reading, self-reflection and therapy.

My father divorced Vickie in 1998, and he passed away in 2012. Vickie remarried and from what I hear, is cheating. I wish she would have sought help for whatever childhood haunts keep her in that self-destructive cycle. To make matters worse, I now have a good friend who’s been hoodwinked by his own version of Vickie. Did I warn him? Yup. Did he yell at me and cast me aside? Yup. It’s as if I’m reliving my childhood, watching my friend instead of my father, heading for a fall.

My hope for my friend, who usually has a keen bullshit dectector, is that he will wake up before too much damage has been done. But, similar to Vickie, his enchantress is pretty, fit, and an amazing liar. Friends tell me, “Don’t worry. She’ll hang herself. And then you can say, ‘I told you so.'” Problem is, I’m not going to say I told you so. I’m going to be there for my friend if he feels had can confide in me. Keep your fingers crossed.